Contemporary Sacred Art Biennial 2014

Cain and Abel: Am I My Brother’s Keeper?

December 6, 2014 - February 8, 2015

The Jubilee Museum & Catholic Cultural Center inaugurated its first contemporary sacred art biennial in 2014. The biennial was a juried exhibition and its theme for 2014 was Cain and Abel, Am I My Brother’s Keeper?

The biennial was designed to bring together contemporary Judeo-Christian artists from a broad range of denominations who have a passion for the visual arts and have made their faith central to their work. Our museum hopes to contribute to a greater Judeo-Christian presence in the art world.

In order to communicate the message entrusted to her by Christ, the Church needs art…Art has a unique capacity to take one or other facet of the message and translate it into color, shapes and sounds which nourish the intuition of those who look or listen.

-Saint John Paul II

The juror for the biennial was Dr. James Romaine, Associate Professor of Art History at Nyack College in New York. He is a frequent lecturer on faith and the visual arts and has authored numerous articles in publications like Image: A Journal of the Arts and Religion and The Princeton Theological Review. Dr. Romaine is the president and cofounder of the Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art (ASCHA) www.christianityhistoryart.org.

The Jubilee Museum Contemporary Juried Sacred Art Biennial was open to artists residing in the United States and overseas. All together, the participating 25 artists represent a broad area of the United States: Texas, Wisconsin, Ohio, South Carolina, Missouri, California, Indiana, New Hampshire, Virginia, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Washington, Colorado, Maine, and New Jersey. Also participating in the exhibition was guest artist and Holocaust survivor, Alfred Tibor, internationally celebrated central Ohio sculptor. A diversity of artistic styles was represented in the exhibition, realism, expressionism, abstraction, among others. Each artist has invited the viewer to acknowledge and contemplate the close bond between art and faith.

Contemporary Sacred Art Biennial juror, Dr. James Romaine, awarded first prize to Texas artist Gwen Meharg, for her painting, Eve’s Heartache. Ms. Meharg explained, “As an artist and mother of six, the cautionary tale of Cain and Abel wounds my mother’s heart as I ponder what went wrong. I pray that Eve’s Heartache is received as a story of hope in the midst of sorrow.” First Prize award was sponsored by the Jubilee Museum.

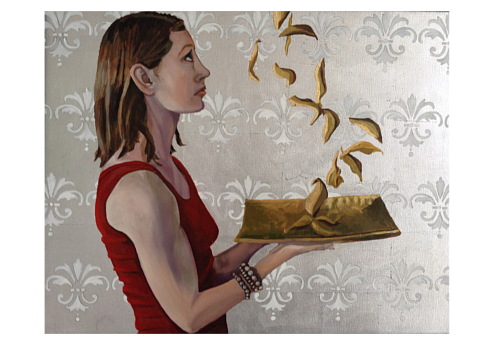

The second prize award was given to Daniel Hall from Indiana for his painting, Minkah: The Gift Offering. Award sponsored by David Meleca Architecture and Angela Meleca Gallery.

New Jersey artist Jean C. Wetta was awarded third prize for her painting, The Caretaker. Award sponsored by Robin & Valerie Coolidge, Wyandotte Winery.

The Contemporary Sacred Art Biennial 2014 was organized by Graziella Marchicelli, the Jubilee Museum’s Director of Museum Services and Special Exhibitions. The Jubilee Museum and Catholic Cultural Center is very grateful to Meleca Architecture, Angela Meleca Gallery, Robin and Valerie Coolidge owners of Wyandotte Winery and Robert Ryan of Egan-Ryan Funeral Home for their generous sponsorship. We are blessed to receive their support.

Art as an Acceptable Offering

By James Romaine, Ph.D.

Now Abel kept flocks, and Cain worked the soil. In the course of time Cain brought some of the fruits of the soil as an offering to the Lord. And Abel also brought an offering—fat portions from some of the firstborn of his flock. The Lord looked with favor on Abel and his offering, but on Cain and his offering he did not look with favor. So Cain was very angry, and his face was downcast. Then the Lord said to Cain, “Why are you angry? Why is your face downcast? If you do what is right, will you not be accepted?”

—Genesis 4:3-7

Cain’s murder of his brother Abel was not his first sin. Cain’s fall from grace, as it is described in Genesis, began with an offering that was unacceptable because it did not properly follow God’s prescriptions. Is there a lesson here for artists, and for all of us?

Artists often think and speak of their art as an offering. The artist creates something from their imaginations and hands. Perhaps the artist is even conscious of their own creativity and talents as gifts from God and hopes to return something as an offering to Him. They hope to hear, “Well done, good and faithful servant!… Come and share your master’s happiness!”

Nevertheless, the example of Cain is instructive. Cain worked the soil, by the sweat of his brow, and brought his produce as an offering. But it was an unacceptable offering. For the Christian making art or looking at art, what makes art an acceptable offering? The artist working today is not under the same set of laws as Cain. However, there are three guiding biblical mandates that may be instructive in considering the question of the visual arts as an acceptable offering. These are: the creation mandate, the community mandate, and the commission mandate.

The Creation Mandate

Where does a biblical understanding of human creativity begin? Perhaps this begins with the knowledge that we are each individually created in, by, and for God. A biblical self-image begins by considering our being created in the image of God. This creation mandate is found in Genesis, starting with Genesis 1:1 “In the beginning, God created…” We are introduced to God first as a creator. Not surprisingly, God’s creation bears His mark and image. This is most clearly articulated in Genesis 1:26-27. Then God said, “Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness… So God created man in His own image.”

In her book The Mind of the Maker, Dorothy Sayers addresses the question of what it means to be a creative person created in the image of God. She interpreted these verses as a description of human creators created in the image of a divine creator. She wrote, “The characteristic common to God and man is apparently… the desire and the ability to make things.” This capacity to create is not the limit of what it means to be created “in the image of God.” However a Christian conception of human creativity and the visual arts draws its initial direction and purpose from the first chapter of Genesis. This mandate affirms that every person is uniquely created by God. Each of us has been created with particular abilities, experiences, and opportunities though which they honor God in their faithful pursuit of his designs and desires. This creation mandate of Genesis is the foundation of a sacramental understanding of the creative person, “in the image of God.”

The creation mandate has both liberties and responsibilities. Having created Adam and Eve, God blessed them and said to them, in Genesis 1:28, and said, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it…” In this first record of God speaking to humanity, he calls us to an act of creation.

The Community Mandate

At times, each of us live and work as if creation and history were just God and us, that our personal relationship with God absolves us of our responsibilities and privileges toward each other and to the world in which we live. Nevertheless, the universe, as created by God, is organically and fundamentally interconnected. In fact, it is this social and spiritual interconnectivity that gives creative action significance. These points of connection are where transformation happens. Therefore, the community mandate is, in part, an extension of the wholeness expressed in the creation mandate. However, the community mandate also recognizes the truth that creation exists in a current state of brokenness because of sin. The community mandate is a challenge to work toward a spiritual unity, founded on creative acts of love.

In the gospel of John 15:9-12, Christ states, “As the Father loved Me, I also have loved you; abide in My love. If you keep My commandments, you will abide in My love, just as I have kept My Father’s commandments and abide in His love. These things I have spoken to you, that My joy may remain in you, and that your joy may be full. This is My commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you.”

This love mandate is critical to a biblical understanding of creativity. Genuinely creativity cannot be motivated by anything other than love. Love is a controlling safeguard that distinguishes creative transformation from other forms of imposed change.

It is noteworthy that Christ gives this command, this love mandate, on the eve of His betrayal by Judas. In his book Life Together, Dietrich Bonhoeffer reminds us that we should not take the gift of Christian community too lightly. He reminds the reader that Christ suffered the loneliness of the cross so that we, sinners deserving that estrangement, might have the community founded on the grace provided in his blood. Bonhoeffer qualifies what he sees as the foundation of a Christian community writing, “We belong to one another only through and in Jesus Christ.” Bonheoffer’s “through and in” suggests that Christ is both the means and end of the community mandate. The community mandate contains both a promise of Christ’s abiding love and a command that we love one another.

The Commission Mandate

A third mandate that has bearing on human creative is found in Matthew 28:18-20, what is sometimes called the great commission. These verses say, “And Jesus came and spoke to them, saying, ‘All authority has been given to Me in heaven and on earth. Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations,.. and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.’” Christ’s promise to always be with his disciples is later fulfilled in the sending of the Holy Spirit.

The commission mandate has both a present-oriented command directing the Christian into the world and an eternity-oriented promise that Christ will complete the work that He has begun. Both the present-oriented command and the eternity-oriented promise have specific implications for art as a medium of spiritual transformation.

It is important to note here that visual arts are unique among the various dimensions of human creativity. Works of art are sacramental in that they are both material and immaterial. The work of art is both visible and invisible. As such, the work of art may not only be a foreshowing of grace to come but it may also be a present, visible, and tangible manifestation of the invisible and eternal kingdom of God.

The commission mandate recognizes that neither the goodness of creation nor the brokenness of sin is history’s final chapter. The final beautiful chapter, for those who are in Christ, is one of redemption and reconciliation. Therefore, the power of an art founded on the commission mandate is not limited to the present but may also have implications for eternity. Works of art not only address the world as it is, they also envision the world as it will be. Not only that, but the work of art may participate in prophetically calling that more beautiful world into being. Although the final completion of this more beautiful world lies in eternity, works of art can be a vision of that future beauty already realized in the present.

The creation mandate, the community mandate, and the commission mandate encourage our commitment to personal, social, and spiritual transformation. We are created in God’s image, for the present purpose of both human and divine community, and with the hope that the future realization of what God is doing in and through us is partially visible in the present. It is within the boundaries of these three mandates, that art is an acceptable offering.

Note:

The essay Art as an Acceptable Offering by Dr. James Romaine was written for the Jubilee Museum’s Contemporary Sacred Art Biennial 2014 Exhibition.

About Dr. James Romaine

The juror for the biennial Dr. James Romaine, is the Associate Professor of Art History at Nyack College in New York. He is a frequent lecturer on faith and the visual arts and has authored numerous articles. Dr. Romaine is the president and cofounder of the Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art (ASCHA).

See also:

Columbus Dispatch: Exhibit’s theme of Cain and Abel a ‘bold choice’

and

2014 CONTEMPORARY SACRED ART BIENNIAL PARTICIPATING ARTISTS:

Michael Buesking (Springfield, MO) www.prophetasartist.com

Zac Buser (Greenville, SC) http://zbuser.com

Lisa K. Cowling (Austin, TX) http://wingsapart.com

Gary Denmon Jr (Numbie, TX) www.gdenmonjr.com

George Geisler (Orange, CA) www.georgegeislerart.com

Daniel T. Hall (Fisher, IN)

Linda Hamilton (Columbus, OH)

Gwyneth Holston (Manchester, NH) http://gwynethholston.com

Linda Hoover (Houstonia, MO) www.lindahooverart.com

Gwen Meharg (Benbrook, TX) www.GwenMeharg.com

Linus Meldrum (Steubenville, OH) www.franciscan.edu/faculty/MeldrumL

Robert Patricy (Columbus, OH) http://robertpatricy.com

Lin Elizabeth Preiss (Spokane, WA) http://linelizabeth.com

Stephen Rountree (Mechanicsville, VA)

Hector Manuel Sagunto (Atlanta, GA)

Cora Smith (Mahaffey, PA) http://kyriegallery.com/joomla/index.php/about-the-artist

Erin Sobony (Columbus, OH)

Julia Stiles (Brownfield, ME) www.juliacstiles.com

Kathy Thaden (Golden, CO) www.thadenmosaics.com

Alfred Tibor, (Columbus, OH) http://alfredtibor.net

Kirsten Van Mourick (San Clemente, CA)

Jean C. Wetta (Island Heights, N.J.) www.jeancarrutherswetta.com

SPONSORS’ LINKS

Meleca Architecture http://www.meleca.com

Angela Meleca Gallery http://www.angelamelecagallery.com

Wyandotte Winery http://www.wyandottewinery.com

Egan-Ryan Funeral Home http://www.egan-ryan.com